Category: business

Make them dance, make them dance.

-

Behind every successful launch, there are 100 interesting failures.

We must stop thinking of failure as an end of something, and learn to see it as a natural part of progress. The first incarnation of a new idea may die, but the best ideas…

-

Too many meetings?

At Automattic, we know our time is finite and precious. Here are the questions we ask ourselves before agreeing to any meeting:

-

Domain harvesting and the Twitter long game in retrospect

Tricking people into seeing unexpected content and converting some of them into customers is a tale as old as the web. It was the perfect model for the takeover.

-

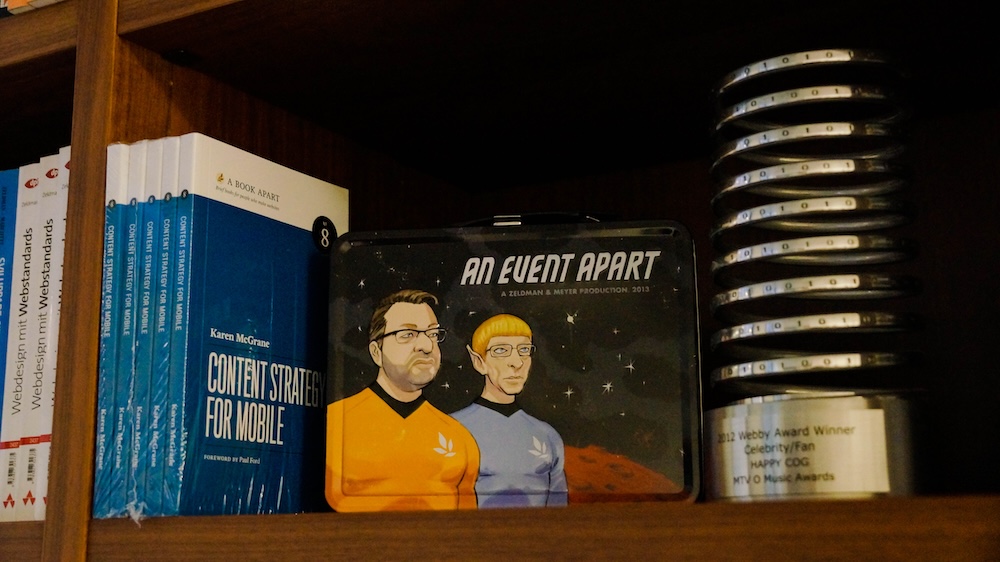

Of Books and Conferences Past

Of books and conferences past: A maker looks back on things well-made but no longer with us.

-

I stayed.

My insight into corporate legal disputes is as meaningful as my opinion on Quantum Mechanics. What I do know is that, when given the chance this week to leave my job with half a year’s…

-

One weird trick

Help to help, because we’re built to help.

-

Ah yes, the famous “intern did it” syndrome

Poachers, when caught stealing content from our website, always blamed the theft on an “intern” or “freelancer.” We always pretended to believe them.

-

Suckage begins here: why search engines now prioritize advertising over good UX

In the dying stages of innovation, companies at the top of the heap use their market power to maintain their high profits.

-

Don’t bring venture capital to a knife fight

Why you can’t build another Apple with VC bucks.

-

Our Lady of Perpetual Profit

A business world with deeply misguided priorities—exemplified by horror stories from the worlds of tech, gaming, and entertainment—accounts for much worker unhappiness and customer frustration.

-

The dogs won’t eat it

My father used to tell this story to his project management students.

-

See me speak: WordPress.com Growth Summit

WordPress.com is holding its first virtual conference, I’m speaking there, and you’re invited. The WordPress.com Growth Summit is a two-day live event where you can learn to build and grow your site, “from start to scale.” To make it…

-

Design Kickoff Meetings

Posted here for posterity: Design kickoff meetings are like first dates that prepare you for an exciting relationship with a person who doesn’t exist.