Category: Career

-

How do you spell success?

Working in tech means being comfortable with change and uncertainty. Successfully working in tech means not letting change and uncertainty paralyze you. Forge ahead on the best information you have, and be prepared to change…

-

Staying relevant

“And in their place came acceptance.” Staying relevant in your profession as you age and technology changes.

-

Of Books and Conferences Past

Of books and conferences past: A maker looks back on things well-made but no longer with us.

-

I stayed.

My insight into corporate legal disputes is as meaningful as my opinion on Quantum Mechanics. What I do know is that, when given the chance this week to leave my job with half a year’s…

-

One weird trick

Help to help, because we’re built to help.

-

Ah yes, the famous “intern did it” syndrome

Poachers, when caught stealing content from our website, always blamed the theft on an “intern” or “freelancer.” We always pretended to believe them.

-

First, be kind.

Your feedback has the power to encourage another person, or shut them down, possibly forever.

-

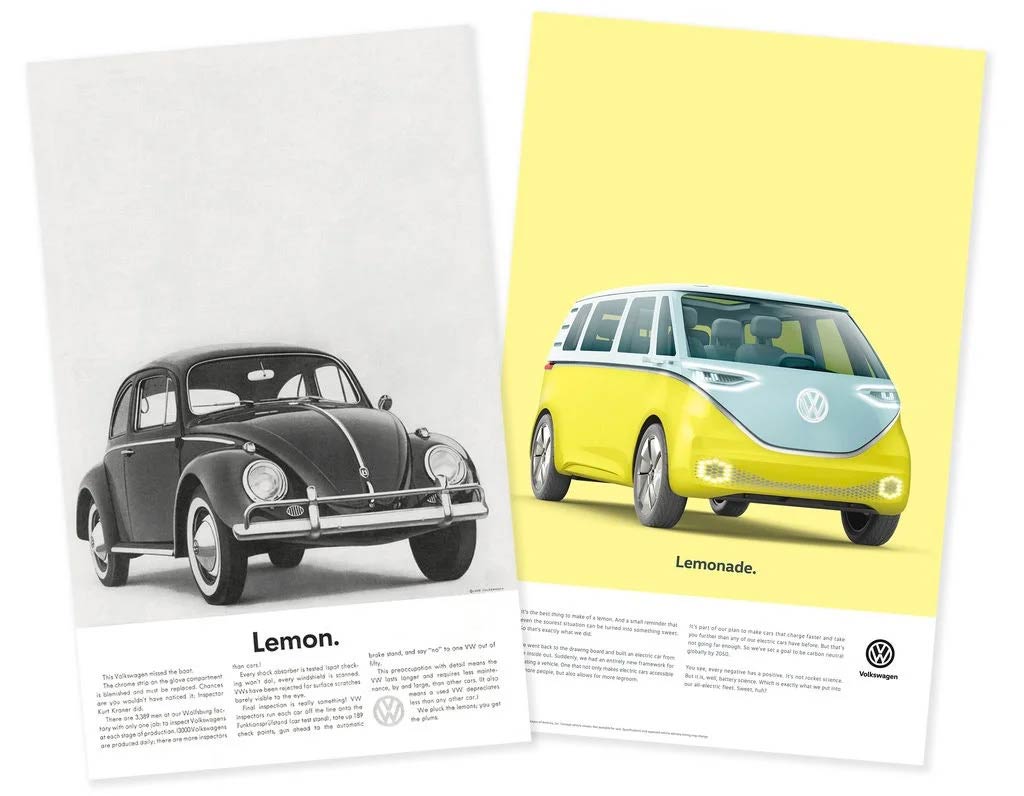

Never give up

The really good designers stand up to the misfortune of a killed idea.

-

The Whims

One of my first professional jobs was at a tiny startup ad agency in Washington, DC. The owner was new to the business and made the mistake of hiring a college buddy as his creative…

-

Design Kickoff Meetings

Posted here for posterity: Design kickoff meetings are like first dates that prepare you for an exciting relationship with a person who doesn’t exist.

-

Design is a (hard) job.

DESIGN WAS so much easier before I had clients. I assigned myself projects with no requirements, no schedule, no budget, no constraints. By most definitions, what I did wasn’t even design—except that it ended up…