Category: Design

-

A die-cut above

Cover art for the 1971 prog-rock LP “Fearless,” by British band Family features a distinctive, die-cut cover design depicting the five band members gradually morphing into a single entity combining features of them all. Tom…

-

What a year that was.

Know your web design history.

-

The salad bar theory of UX professionalism

Less, but better? Not this week.

-

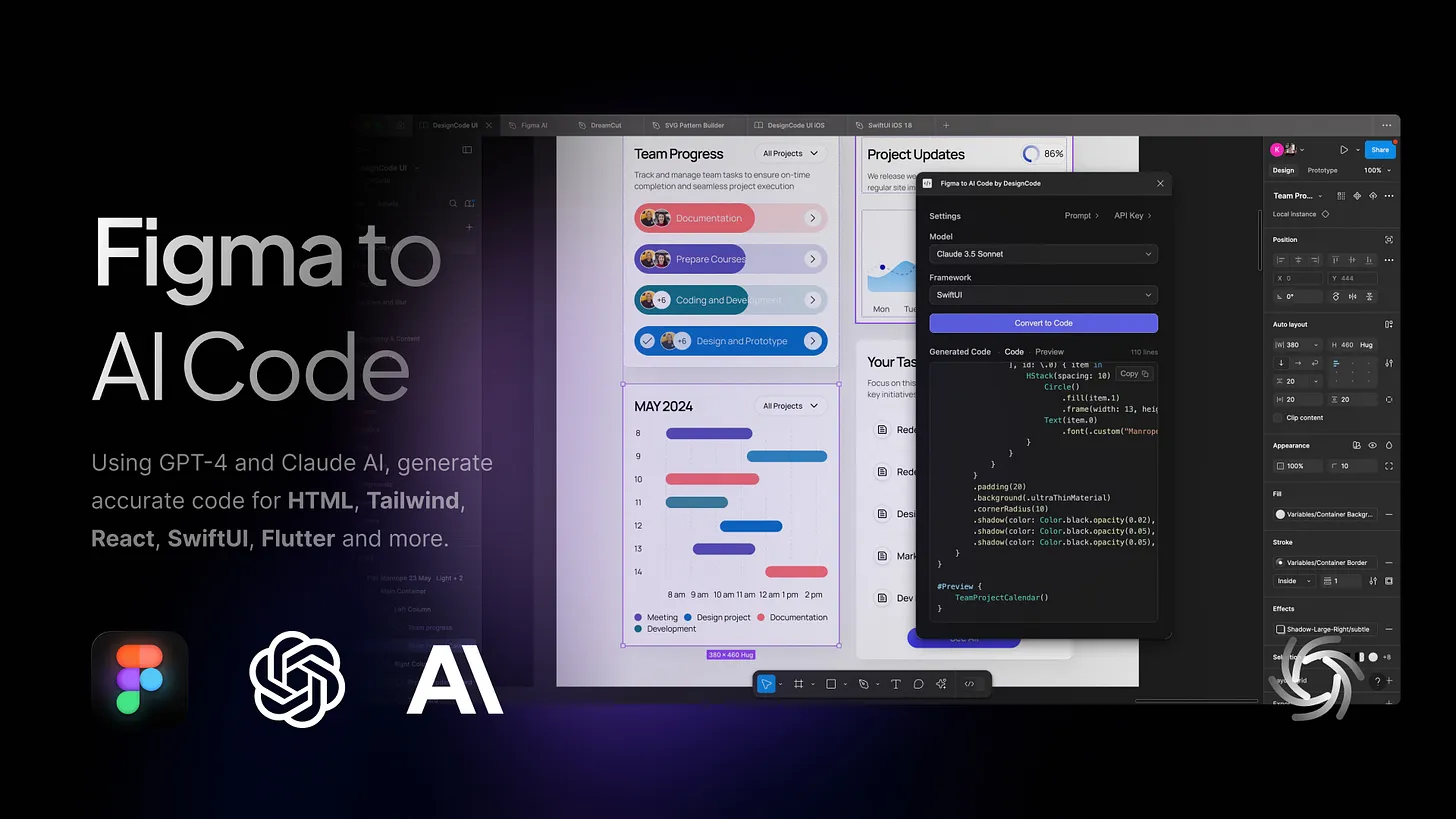

Claude Code for Designers

FIRST, the disclaimers: Some of my favorite writers—folks who are as anti-fascist and pro-democracy as they come—publish on Substack, but I read and recommend their work less and less frequently, because Substack has a Nazi…

-

Accessibility is a human right, cruelty a human wrong.

Once more for the folks in the back. Calibri is easier than Times New Roman for folks with certain visual disabilities to read. That’s why the Biden Administration chose Calibri for their digital communications: to include…

-

Behind every successful launch, there are 100 interesting failures.

We must stop thinking of failure as an end of something, and learn to see it as a natural part of progress. The first incarnation of a new idea may die, but the best ideas…

-

Everybody’s lost it, Part I

My beloved veterinarian’s office apparently moved to a new office location without informing customers. They also changed phone systems. The new phone system doesn’t work, and they didn’t leave a forwarding message on the old…

-

Too many meetings?

At Automattic, we know our time is finite and precious. Here are the questions we ask ourselves before agreeing to any meeting:

-

My Glamorous Life: broken by design.

I encounter broken systems like this almost every week. And probably, so do you.

-

Writing in WordLand

This is a test. This is only a test. I’m using WordLand to write this post to my WordPress website. It’s a new, stripped-down writer’s tool for bloggers. Think of it as a frill-free writer’s…

-

Forever

The first website my colleagues and I created was for “Batman Forever” (1995, d. Joel Schumacher), starring Val Kilmer. That website changed my life and career. I never saw “Top Gun,” but Val Kilmer made…

-

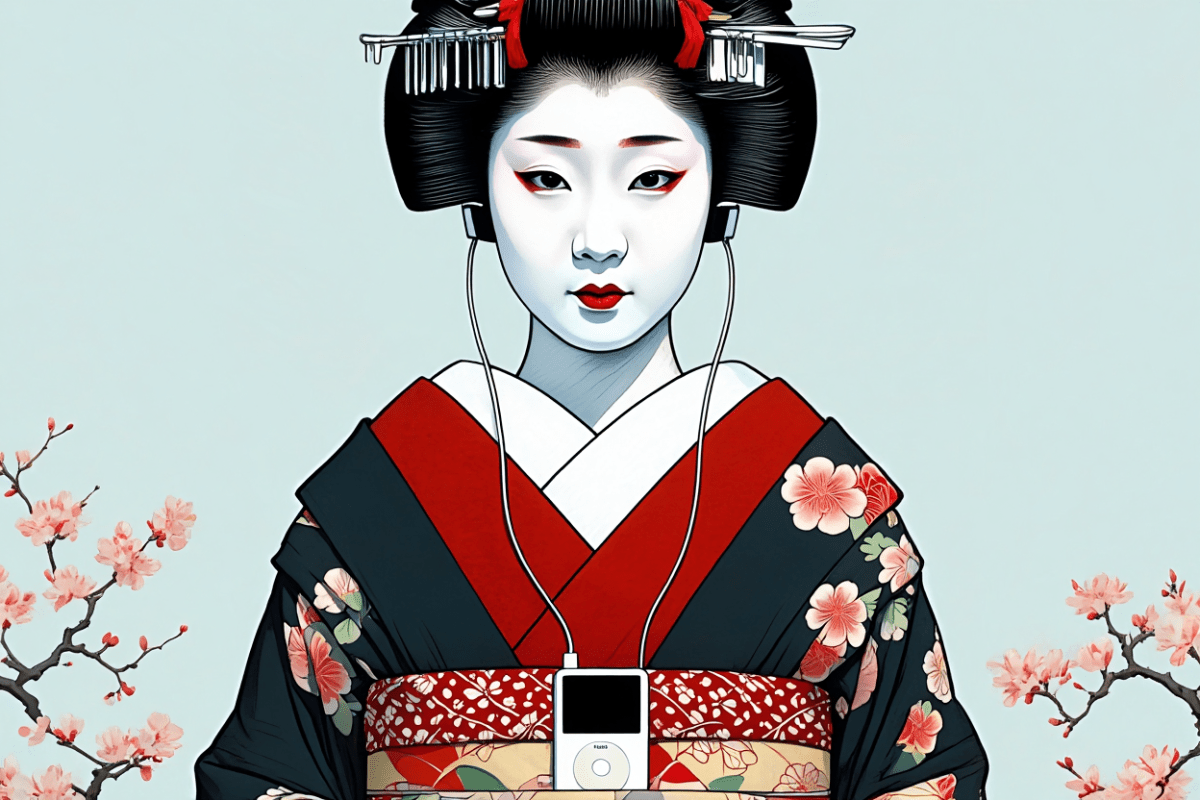

This Years Model

There’s a new AI model that can render photorealistic people and products, including text and logos. Geisha With Walkman is something I tried to draw 40 years ago, but my rendering skills were simply too…