Category: glamorous

My Glamorous Life

-

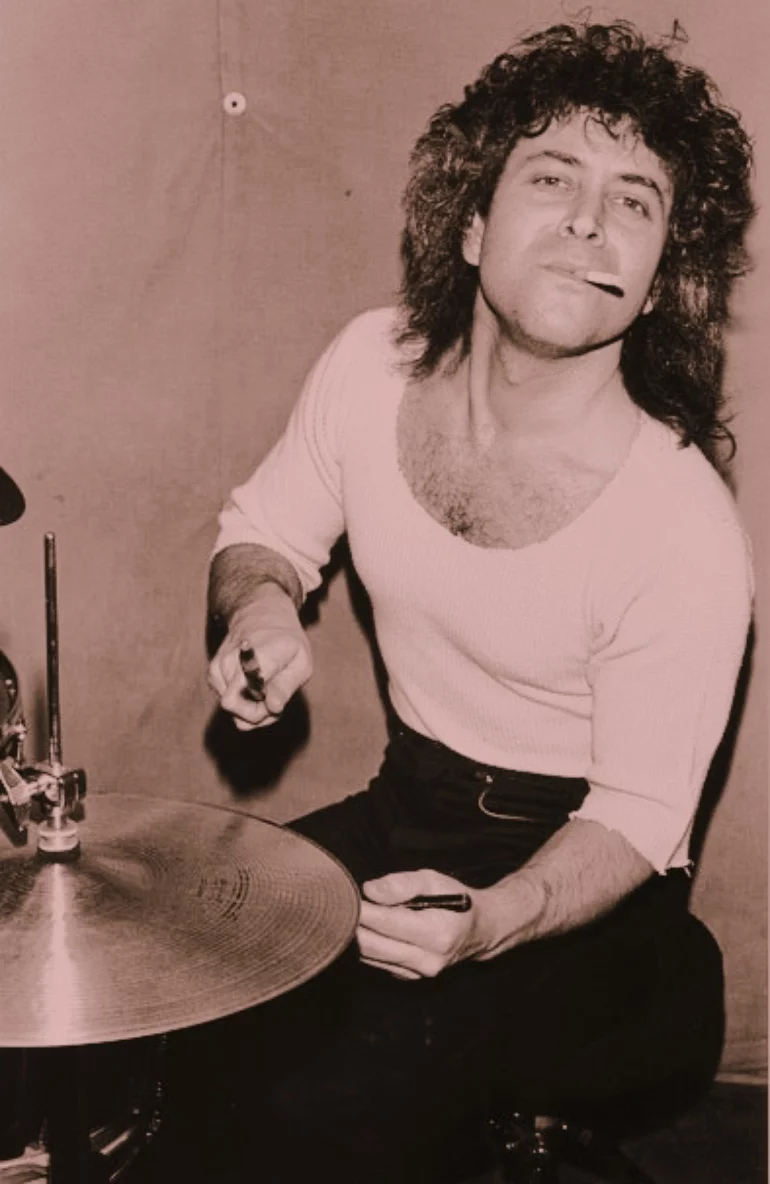

My brother, the rhythmic conceptualist

Remembrance of beats passed.

-

American healthcare

Cooling my heels at the drugstore.

-

My Glamorous Life: Entertaining Uncle George

Fam and I are visiting my 96-year-old Uncle George tonight. We love him. His complicated and somewhat meandering stories have been music to my daughter’s ears since she fell asleep in a cab at age…

-

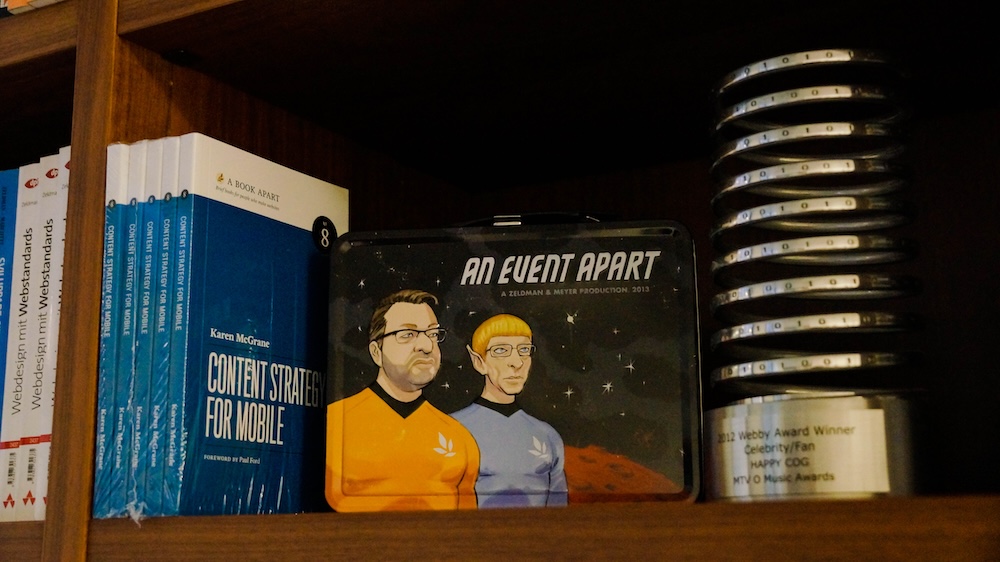

My Glamorous Life: Bots, Books, and Betrayal

My father was an engineer who designed robots. When I first learned what he did, I imagined the Robot from “Lost in Space,” and asked him to make me one. When I turned 13, I realized…

-

Staying relevant

“And in their place came acceptance.” Staying relevant in your profession as you age and technology changes.

-

The eye of God

My doctor sends me to Brooklyn for an abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. As instructed, I fast for six hours beforehand. I don’t even brush my teeth, for fear of swallowing toothpaste and screwing up the…

-

My Glamorous Life: broken by design.

I encounter broken systems like this almost every week. And probably, so do you.

-

A morning’s tale

Instead of screaming, I turned on the faucet.

-

My father, Maurice Zeldman, and his ZGANNT software

I asked Claude to write about the career of my father, the inventor Maurice Zeldman, as if I’d written it myself. Here, with no edits by me, is what Claude said.

-

Forever

The first website my colleagues and I created was for “Batman Forever” (1995, d. Joel Schumacher), starring Val Kilmer. That website changed my life and career. I never saw “Top Gun,” but Val Kilmer made…

-

Who turned off the juice?

The whole 90 minutes, my brain’s shrieking, “You’re having a panic attack!”

-

My Glamorous Life: The Unexpected Samples

If you’ve never fallen gently asleep to jazz ballads, only to sit bolt upright because a horse is shrilly whinnying in your ears, you should try it some time.

-

Far from the bullying crowd

The bullies who beat and mocked me in eighth grade were cruel and stupid. They despised intelligence and worshipped violence, although they would settle for athletic ability. The school blessed their thuggery by scheduling dodgeball.…