Category: industry

This web business: culture and concepts.

-

The salad bar theory of UX professionalism

Less, but better? Not this week.

-

We named them after the humans they were replacing.

“The word ‘computer’ only really slid over to mean ‘a machine’ in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, once we started building mechanical and then electronic devices to do that work instead [of people].…

-

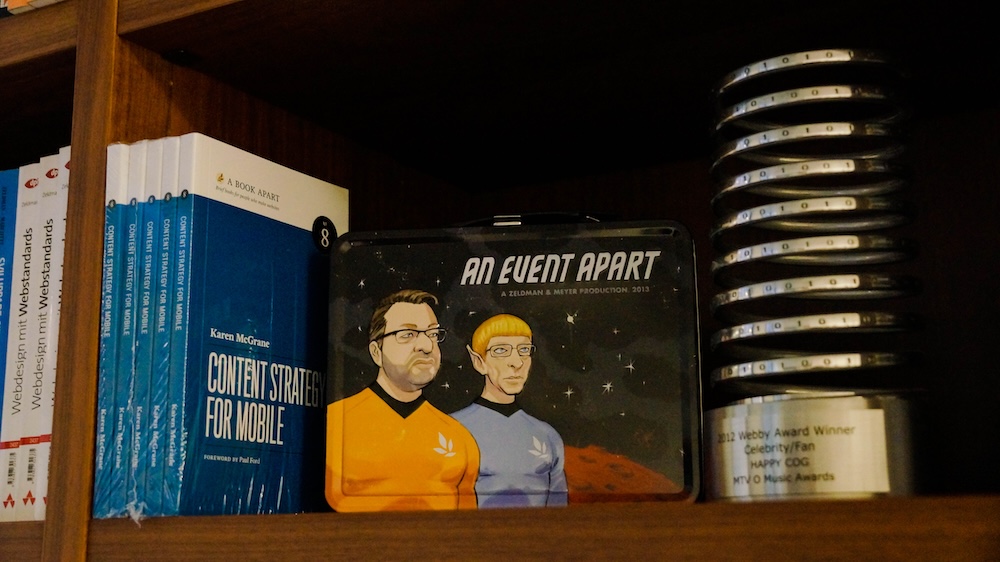

Of Books and Conferences Past

Of books and conferences past: A maker looks back on things well-made but no longer with us.

-

Our Lady of Perpetual Profit

A business world with deeply misguided priorities—exemplified by horror stories from the worlds of tech, gaming, and entertainment—accounts for much worker unhappiness and customer frustration.

-

Get it right.

“Led” is the past tense of “lead.” L.E.D. Not L.E.A.D. Example: “Fran, who leads the group, led the meeting.” When professional publications get the small stuff wrong, it makes us less trusting about the big…

-

Algorithm & Blues

Examining last week’s Verge-vs-Sullivan “Google ruined the web” debate, author Elizabeth Tai writes: I don’t know any class of user more abused by SEO and Google search than the writer. Whether they’re working for their…