Category: State of the Web

-

Mark your calendar: Local News Day is 9 April

It’s no secret that newspapers across the country exist in a fragile ecosystem. Automattic has long supported journalism and local media with investments in publications and platforms like Longreads, The Atavist, and Newspack. We believe that local news…

-

Receipts: a brief history of the death of the web.

They say AI will replace the web as we know it, and this time they mean it. Here follows a short list of previous times they also meant it, starting way back in 1997. Wired:…

-

Your opt-innie wants to talk to your opt-outtie.

Scrapers gonna scrape.

-

Domain harvesting and the Twitter long game in retrospect

Tricking people into seeing unexpected content and converting some of them into customers is a tale as old as the web. It was the perfect model for the takeover.

-

Of Books and Conferences Past

Of books and conferences past: A maker looks back on things well-made but no longer with us.

-

Web Design Inspiration

If you’re finding today a bit stressful for some reason, grab a respite by sinking into any of these web design inspiration websites.

-

Our Lady of Perpetual Profit

A business world with deeply misguided priorities—exemplified by horror stories from the worlds of tech, gaming, and entertainment—accounts for much worker unhappiness and customer frustration.

-

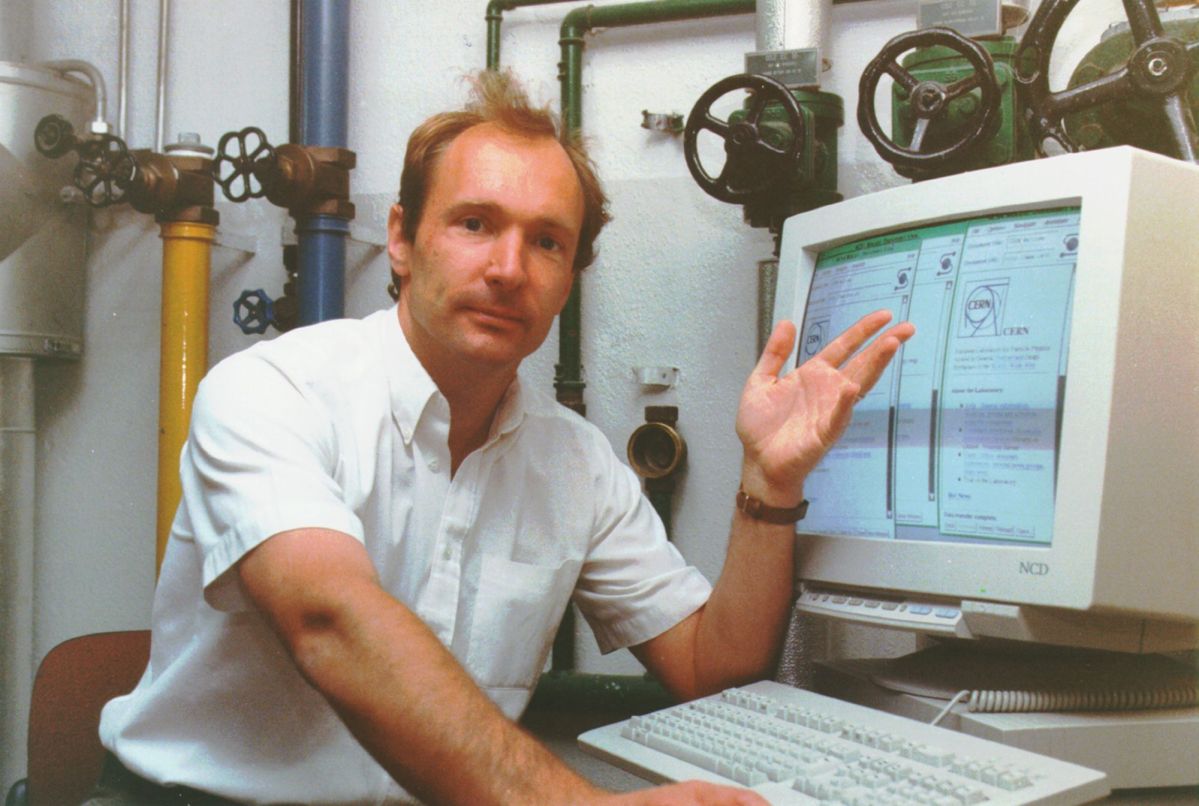

Heal an ailing web

Leadership, hindered by a lack of diversity, has steered away from a tool for public good and one that is instead subject to capitalist forces resulting in monopolisation. Governance, which should correct for this, has…